Other Technology

KITT Car Scanner

- Introduction

- Schematic

- Construction

- PCB Procedure

- PCB Supplies

Easy PC Boards Using Laser Printers

A printed circuit board (PCB) makes your project smaller, more tidy and more reliable. It also allows others to easily duplicate your work. How do you make a PCB?

Your laser printer can make the mask for your own high-quality PCBs. It requires the correct

paper type and a clothes iron. With practice, you can

have finished boards in a few hours and the cost is quite low.

Your laser printer can make the mask for your own high-quality PCBs. It requires the correct

paper type and a clothes iron. With practice, you can

have finished boards in a few hours and the cost is quite low.

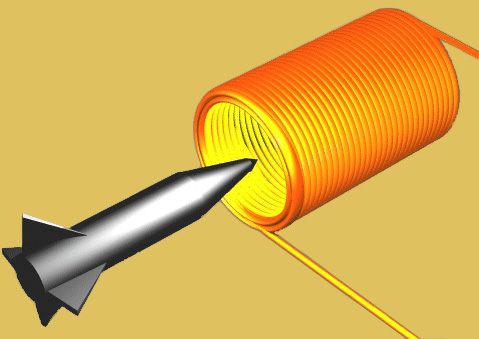

This toner transfer method works because toner is plastic. And the etching chemicals (acids) will dissolve copper but not plastic. Very small trace-widths are achievable, down to 0.01 inches wide or less.

Here are Barry's notes, adapted and condensed from Tom Gootee's excellent instructions.

Create Copper Side Pattern

Create the copper-side pattern with your favorite drawing program. You can save money using MS Paint, and save time using a graphics package that supports layers such as Adobe Photoshop or Corel Paint Shop Pro. If you're just starting out, it's a good idea to use a real PCB or CAD (computer-aided design) program, since it automatically takes care of resolution (pixels per inch) and component size and placement.

Note whether the pattern is drawn 'reversed' or not. In my case, I draw the pattern as if I'm looking down through the PCB from the component side. When it's done that way, flipping the paper over for the ironing step, below, 'reverses' the pattern onto the upside-down board's copper side. And then when the board is turned component-side up, the pattern on the board is oriented how it was intended to be.

When I put text on the copper-side pattern, I have to use reversed text (flipped left-to-right), for it to be readable on the finished board. Most graphics software has simple 'image-reversing' features, which usually work on just a selected piece of text.

And: the drill-holes' location-markers, on the solder pads, were made by drawing squares, with sides with lengths of 6/300 of an inch (i.e. 1/50th of an inch).

Print PCB Mask

Print the pattern using the darkest laser printer settings (On a LaserJet 4 use: Dithering: NONE, Intensity: DARKEST, 'Raster Graphics', 'Print Truetype as Graphics', and RET (Resolution Enhancement Technology): OFF).

Never touch the board-part of the pattern paper with fingers, or with anything else, before or after it's been printed.

Cut out the pattern using scissors or a paper shear, as close as possible to the pattern on three sides. Leave an inch or more on ONE of the shorter sides for handling. Lay the pattern flat, face-up, until it's ready to be used.

The smallest trace-thickness that is shown is 4/300ths of an inch (about 0.0133 inch, or 0.000523 cm). And, at the top of the photo, some of the traces are separated by only 2/300ths of an inch. (It doesn't show up very well in this photo. But it works well in actuality.)

Cut the PCB Material to Size

For cutting the PCBs to size, a big metal shear is ideal.

A bandsaw would also work great. You might need the appropriate fine-tooth blade, maybe even one for cutting soft metals (although the thin copper hardly counts as 'metal', as far as cutting-tools are concerned).

Also a small common hand-held reciprocating-type jigsaw, with a metal-cutting blade installed will work fine.

A hacksaw is also satisfactory, although it can be challenging to cut a perfectly straight line.

A table saw, or a 'cutoff saw', or a 'radial arm saw', seem like they might work well, too, with a thin, fine-toothed blade.

After cutting, use a metal file or fine sandpaper to ensure edges are smooth and that they don't protrude above the rest of the copper surface. A small, fine-grooved 'mill bastard' file works well.

Prepare Bare PCB

Scrub the board with a Scotchbrite or 'artificial steel wool' pad (nylon abrasive pad), equivalent to '0' steel wool, in two orthogonal directions. At the end, use a lighter pass or '000' equivalent so it's not too rough. Do not use real steel wool, since it will cause rust and oxidation, after it's embedded in the copper.)

The scrubbing with Scotchbrite does TWO things: 1) It removes oxidation, stains, scratches, etc, so the copper surface of the PCB is all uniformly nice and shiny. (You might have to press very hard, for this part.) And, 2) It makes the copper surface somewhat LESS than perfectly smooth. The nylon abrasive pad makes many tiny scratches in the copper. This apparently helps the toner to stick to the copper.

Scrub the board with acetone solvent soaked into a paper towel. Continue until almost no more discoloration is seen on the paper towel. Press hard! And keep switching to clean parts of the towel.

Lay the board (with the copper side facing up) on a rigid, flat, heat-resistant surface, such as a smooth piece of wood or plywood. Blow any dust, etc, off of it, if necessary, very carefully, and off of the pattern paper. Lay the paper pattern face down on the copper, lining it up exactly right.

Iron Pattern onto Copper

Use a regular handheld household electric clothes iron, set as hot as it will go, i.e. the MAXIMUM temperature setting (called 'Linen', on mine, just above the 'Cotton' setting), with no steam.

Place the iron on the back of the pattern. Heat the whole board. i.e. Hold the iron on the whole pattern, if possible (unless the pattern is too large), for at least 1/2 minute or more, pressing firmly (see addendum, below, for pounds of force used). I usually am standing next to a 30-inch-high table that the pcboard is on, and just 'lean on' the iron, somewhat, during this step.

I usually move the iron a little bit, after about half of the time has passed, just in case the holes on the bottom of the iron, or some other factor, might cause a non-uniformity problem.

Note that almost as soon as the iron first touches the pattern and presses it against the board, the pattern will no longer slip on the copper. So, sometimes I put the iron on a small portion of the pattern (a corner, or the smaller end of a board, usually), at first, for five or ten seconds, while I hold the pattern in position with my other hand. This prevents the pattern from slipping, just as the iron is applied, especially if the pattern paper is slightly curled, or the iron is applied too slowly, or with some lateral motion, etc etc.

After the board is well-heated (after the 1/2 minute or more, in the previous step), I place the rear of the iron along an edge of the board (with the rest of the iron on the board), and press hard near the rear of the iron's handle. I move the iron 1/4 to 1/2 inch away from the edge and press hard again, for about a half-second to a second, and continue that way until I'm near the other side of the board (with the rear of the iron), and it gets ha the other way (starting from the opposite edge), doing the same thing, over the same part of the board. If there are board-edges that are wider than the iron's rear edge, I make overlapping passes, with the iron's side being along the outer edge of the board, on both sides of the wide edge. I usually do this whole procedure starting from each of the four edges of the board.

I then always go over the whole board with the tip of the iron, keeping it flat but torquing the iron 'forward', as I go, moving either side to side on the board or pulling the iron backwards, in lines about an inch or less apart, across the whole board. But I'm careful to never let the tip 'gouge' or 'dig in', and never let any edge of the iron press against the board by itself. i.e. I always try to keep the bottom of the iron flat against the board, no matter what else I'm doing.

If you see the pattern starting to show, through the paper, then you have probably done it well-enough. (Or is that just some kind of black stuff from the bottom of my iron rubbing off onto the areas over the slightly-raised pattern?)

At the end, I usually reheat the board (with pressure on the iron at the same time, again). I also usually just press the iron flat against the board, hanging almost halfway off one side, then in the middle, then off the other side (still always keeping it flat against the board), for good measure...

The entire heating/ironing process usually only takes between two and three minutes.

Soak Board and Remove Paper

Then, usually within five or ten seconds or so, I pick up the board (i.e grab it by the edge of the pattern paper) and drop it into hot water. [A minute or two of delay doesn't seem to matter, at this point.]

I usually use a small rectangular glass baking dish (or a sink), full of hot water (about 130 deg F or more; mine is usually about 140 degF), letting the board soak for 10 or more minutes.

Peel off the paper, or at least the top layer or two. If the paper underneath is still a little dry-ish, put the board back into the water, for another ten minutes or more.

After the boards soak for 5 or 10 minutes, you can peel off at least one layer of paper and let them soak for another 10 minutes or more. The last layer of paper doesn't ever peel off in one piece. But that's OK! You can rub it almost as hard as you want, with either your thumbs or a toothbrush, and you won't hurt the traces! [After I had made the first couple of boards using the Staple paper, I started going to the toothbrush sooner. Mine was a soft (or maybe medium) stiffness brush. But I could use circular or straight motions, pressing almost as hard as possible, with absolutely no noticeable damage to the traces.]

Rub the remaining paper off with thumb pressure (or a toothbrush or other soft brush). It's OK to rub hard. But your thumbs' skin may get sore. Usually, almost all of the paper residue comes off, even off of the toner itself. So, you could SEE if there were any pinholes, etc, in the toner. (I have yet to see any defects, though, using the Staples Picture Paper.) Note that it doesn't matter if there is paper residue that remains on top of the TONER.

At this point, if something has gone wrong, you can start over and not waste the board, by washing the board with laquer thinner (see below), to remove the toner. Then, begin again with the second (Scotchbrite) step, above.

Use small circular motions with a toothbrush, or some other small, relatively soft brush (but not with metal bristles!), to remove paper residue from small or tight areas, and, especially, from the drill-hole 'marks', and any small text. This used to be the hardest, or most tedious, part. But with the Staples 'Picture Paper', this step isn't too bad, at all. And you can usually rub pretty hard, with the brush, without damaging the toner at all (unless you didn't iron it correctly). Small circles with the brush, keeping the bristles mostly un-bent, and using their tips to dig into areas that need it, seems to work well.

Rinse the board and wipe the board dry with a clean paper towel. [Update: Now I usually wash it with soap and warm water, and then rise and dry it, just to make sure that all of the paper's residues have been removed, pretty well.]

I tried leaving the paper residue IN the holes and etching. But the result was less than satisfactory. So, in order to minimize the potential for damage to the traces from hard rubbing with the brush, I tried letting a board soak overnight in water. Voila! The drill holes were easily cleaned out with fairly light scrubbing with the toothbrush. Of course, I usually can't wait overnight. Adding some liquid dish detergent helps, if I'm in a hurry. Also, digging the bristles on the tip of the brush straight into the holes, while lightly making tight circular motions, gets the residue out with minimal brush pressure. It is still quite tedious, if there are lots of holes.

Touch-Up Board with Sharpie

Make any necessary corrections to damaged toner, using a Sharpie or other etch-resistant marker pen.

I sometimes have a couple of very small flakes of toner fall off, on about one out of three or four boards, at the most, especially if I scrub way too hard with the toothbrush. The Sharpie will fill in small holes in the toner.

Etch PCB

Use Ferric Chloride in a tupperware-style plastic food container, in a sink of hot water.

You can agitate it by rocking the container. Or, use latex gloves and hold a pcb in my hand and either sweep it back and forth in the etchant, or, hold it flat and push it up and down vertically.

Keep an eye on the progress of the copper removal and sometimes rub on the areas where the removal seems slower, with my thumb or fingers. I have also been told by one person that they just used a balled-up paper towel with some etchant on it, and rubbed the board until all of the copper was gone, with very good results, although I've never tried that method, myself.

Don't get the etchant on anything else, especially a good stainless-steel sink(!) (or your clothing). I keep the lid loosely on the container, to catch any splashes. Don't use a metal container! And don't use any metal utensils, if you want to use them for anything else, ever again! Wipe and flush any accidental spills with lots of water, immediately. The ferric chloride will also stain your skin. Wash it off immediately, if possible.

Note that if you use '1-ounce' copper boards, instead of '2-ounce', etching is much faster, and, correction-pen marks will last long-enough to work well. Plus, over-etching isn't usually as much of a problem.

When etching is almost complete, I used to remove the board, rinse it under running tap water, and put it in a small tub of half-strength etchant (diluted 1:1 with tap water), and lightly brush the areas that still had visible copper, until they had been removed. This seems to help prevent over-etching. [Update: Now I usually just wear latex gloves and rub the board with my fingers, in the full-strength etchant tub, to remove any stubborn areas.]

When I do one board at a time, I sometimes use a plastic tub of etchant, which sits in hot water in a sink. I wear rubber gloves and hold the board with my hand, continuously swishing it around in the etchant (no splashing, hopefully). I also usually rub my (gloved) fingers on the parts of the board that are etching more slowly, which speeds the copper's removal a little, in those areas. Every once in a while, I remove the board, rinse it, and hold it up to a bright light (and also reflect light off of it), to better-see what's left to remove. Etching for too long a time (any longer than absolutley necessary) can tend to degrade the quality of the finished board's tracks, especially their edges.

Clean Toner from PCB

Wash the board in Laquer Thinner solvent, rubbing with a paper towel, to remove the toner quickly.

Be careful: Laquer thinner is *extremely* volatile and flammable and explosive! Do it outside.

Put a small amount of thinner in a paper towel. Wipe the board clean, turning the paper towel frequently.

Drill Holes in PCB

Drill the holes (if your PCB is for through-hole components, as opposed to the newer surface-mount). The etched hole marks help guide the drill bit, especially on small pads and when holes are very close together, or when the drill bit is a little wobbly.

I used to use a regular floor-standing drill press, set at its highest RPM (revolutions per minute). I had tried the solid-carbide PCB bits, about .035 inches, with the larger, 1/8-inch shanks. But they are so strong that they're too brittle, and they broke too often, for me. (Even getting 50 of them for $5 at a hamfest didn't seem like a good deal. That's how often I broke them!) So, I usually just got the 'wire-gauge' high-speed steel drill bits, from the local hardware store. I'd been using the #60 (.04 inch), since they fit a large variety of component lead sizes (all but the largest). I got 15 bits for about $20. I changed bits every few hundred holes, at the most, or whenever I noticed the edges of the holes were getting pulled away from the board too much. I guess the FR-4 board material doesn't transmit heat well at all, and the steel bits get hot quickly, and consequently dull rather quickly.

Many people have had good success using a Dremel tool, with the Dremel drill-press/stand adapter. At least one person reported also using a large magnifier, at the same time. This would also help give eye-protection. Otherwise, safety glasses (eye protection) should be worn.

Add Component Diagram to PCB

If you're going to put artwork on the component side of the board [Recommended(!), especially since it's so easy to do; much easier than doing the copper side.], scrub it with the Scothbrite pad, at this point, with the same method that was used for the copper side. Then do an 'acetone rub', with a paper towel, until no more dirt comes off, as was done for the copper side. Make sure the holes are all dried out. (Tapping each edge of the board sharply on a hard surface can help to dislodge any liquid that's still in the holes. Then re-dry and allow to air dry for a minute.)

Note that the pattern has to be drawn as the reverse image of what it will look like after it's applied to the board.

Hold the board and the pattern sheet together (usually printed on the other, more-easily-removed, 'JetPrint Multi-Project' paper, mentioned above) in front of a very bright light, to align the component markings with the holes' pattern. (If your boards aren't translucent, this method may be a problem.) Then iron the component-side pattern onto the fiberglass side of the board, using the same technique as was used for the copper side.

Soak for five or ten minutes in warm water and then just peel off the paper. Rinse and lightly rub the very minimal residue away, dry the board (and maybe wash with liquid soap and warm water), and it's ready!

| < Previous | Page 4 of 5 | Next > |

©1998-2024 Barry Hansen